|

While attending a conference in Budapest, Sandy Norris, a pharmacologist from

Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan, detoured from the lectures to visit the Royal Palace,

once home to the Hapsburgs. After walking through cold, darkened hallways, she came

upon a small courtyard enclosed by an intricate glass and wrought-iron dome.

"I loved the way it was filled with sunshine and warmth," she says. "It was exactly

the feeling I wanted in my own home."

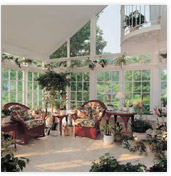

Norris' 1920s brick French manor house had an H-shaped footprint with the living and

dining rooms occupying separate wings across a courtyard. "You had to walk from the

central hallway to each of the formal areas," she says. To connect them and brighten

up the floor plan, she turned to the same solution the Hapsburgs employed more than a

century ago, adding a little glass palace of her own-a light-drenched space called a

conservatory.

Today, these architectural confections from the 19th century have become an upscale fad.

"Done well, conservatories add a striking measure of grace and even whimsy to a home, the

way that a cupola or widow's walk does," says Madison, Connecticut, architect Duo Dickinson.

"They're the rich man's screened-in porch, with far more stature and versatility.

Today, these architectural confections from the 19th century have become an upscale fad.

"Done well, conservatories add a striking measure of grace and even whimsy to a home, the

way that a cupola or widow's walk does," says Madison, Connecticut, architect Duo Dickinson.

"They're the rich man's screened-in porch, with far more stature and versatility.

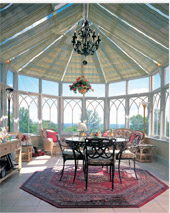

What distinguishes conservatories from ordinary sunrooms are their glorious architectural

embellishments, ranging from Baroque finials and pediments to arching Gothic structural supports.

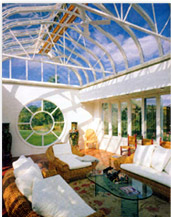

Yet despite their apparent antiquity, modern technology in the form of ceiling shades, automatic

shutters and climate control systems allow conservatories to serve comfortably as dining rooms,

living rooms, party rooms, breakfast rooms and even swimming-pool enclosures. In fact, it's the

rare conservatory that is actually used for growing plants. A British rock star, for instance,

uses his as a private den. "It's the only room his wife allows him to smoke in," says Paul Zec of

Amdega/Machin Conservatories in Westport, Connecticut, who installed it (complete with roof made of

high-impact polycarbonate plastic in place of glass). Another of Zec's clients, a Broadway composer,

had a conservatory specially built for his pet African tortoises; he calls it a "tortorium."

What distinguishes conservatories from ordinary sunrooms are their glorious architectural

embellishments, ranging from Baroque finials and pediments to arching Gothic structural supports.

Yet despite their apparent antiquity, modern technology in the form of ceiling shades, automatic

shutters and climate control systems allow conservatories to serve comfortably as dining rooms,

living rooms, party rooms, breakfast rooms and even swimming-pool enclosures. In fact, it's the

rare conservatory that is actually used for growing plants. A British rock star, for instance,

uses his as a private den. "It's the only room his wife allows him to smoke in," says Paul Zec of

Amdega/Machin Conservatories in Westport, Connecticut, who installed it (complete with roof made of

high-impact polycarbonate plastic in place of glass). Another of Zec's clients, a Broadway composer,

had a conservatory specially built for his pet African tortoises; he calls it a "tortorium."

The fancy conservatory actually sprang from the more humble English plant-growing hothouse, in particular

those designed by Joseph Paxton in the mid-1800s. While working as the chief horticulturalist on the

estate of the Duke of Devonshire, Paxton managed to secure a clipping of a gargantuan African water lily,

with leaves 12 feet wide. Inspired by their pronounced veins, Paxton built an elaborate greenhouse with

exposed iron supports to house the giant. The next year, in 1851, he magnified this design to create one

of the world's most beautiful buildings, London's Crystal Palace, the setting for the world's first international exposition.

Although the building contained some exhibits that were eye-popping for their day-including a stuffed elephant from

Colonial India and a heating stove built to resemble a knight's armor-what captivated Victorian visitors most was

the palace itself, a glass-and-iron wonder that was nearly a third of a mile long. Some critics questioned the

building's architectural merit (one compared it to "a cucumber framed between two chimneys"), but today, it is

generally regarded as one of the most original, provocative designs ever built.

Although the building contained some exhibits that were eye-popping for their day-including a stuffed elephant from

Colonial India and a heating stove built to resemble a knight's armor-what captivated Victorian visitors most was

the palace itself, a glass-and-iron wonder that was nearly a third of a mile long. Some critics questioned the

building's architectural merit (one compared it to "a cucumber framed between two chimneys"), but today, it is

generally regarded as one of the most original, provocative designs ever built.

For the next half century, the Crystal Palace spawned a conservatory boom of its own. Yet for all their beauty, the

conservatories of old had a fatal flaw: single-pane glass, which has all the insulating capabilities of a sheet of paper.

This meant the enclosure would get uninhabitably hot when the sun shone directly on it, then turn uncomfortably cold at night.

"The temperatures inside could fluctuate 30 degrees or so over the course of a single day," says Zec. "That made it

impossible to connect them to a house and use them as living spaces without overloading the heating and cooling systems."

The advent of double-pane or insulated glass changed all that by buffering temperature extremes and making it possible to

attach a conservatory to a house without sacrificing comfort.

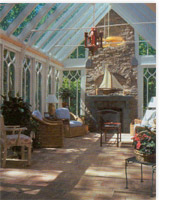

Double-glazing, however, was only a partial solution to overheating. In all-glass conservatories, heat can be further controlled

with the addition of shades that cover the entire ceiling and greatly reduce incoming sunlight. A combination of overhead vents

and side windows can create natural ventilation, and ceiling fans can add to the flow of cooling air. The vents can even be rigged

with sensors and motors that react to the indoor temperatureand also close automatically when they detect rain. But, however it's

ventilated, using a conservatory to grow plants will put a lot of moisture in the air, which can result in making the space

incompatible with other uses. "If you try to put a Steinway in with a bunch of orchids, it'll need tuning every other week," says architect Dickinson.

|

|

Positioning the conservatory can also help to beat the heat. "If you face it due south, you'll have a harder time keeping it cool in

the summer no matter what you do," says Zec. Adding shades will help, as will planting deciduous shade trees outside or tinting the

glass. An even better approach would be to position the conservatory so it faces either the morning sun in the southeast or the

afternoon sun in the southwest. Another possibility is to have a partial shingle, or metal roof instead of one made of glass, which

turns the conservatory into something closer to what the French call an orangerie-a kind of greenhouse originally used to cultivate

oranges in cool climates. "A lot of light comes through even with a partial roof, and you end up with a room that has a much milder

temperature," says Mark Barocco of Renaissance Conservatories in Leola, Pennsylvania. "As we gain experience with conservatories,

we seem to be using less and less ceiling glass."

That is what Sandy Norris chose back in Grosse Pointe Farms. Having visited several conservatories, Norris knew the pitfalls of summer heat.

"I wanted mine to serve as a formal dining room, not a hothouse, so I had to be careful," she says-especially since she intended to furnish

the room with her collection of 17th century European antiques. Instead of a full glass roof, she opted for a 16-foot-by24-foot orangerie

style room. The ceiling has a 5-foot-wide glass perimeter that surrounds a flat, copper-topped roof section. When summer heat builds up,

air-conditioning fights back through four ducts. In cold weather, comfort comes from hot-water radiant heating tubes that loop under the

limestone floor. "In the winter, I love to lie down on the warm floor and watch the snow falling against the glass in the ceiling,"

she says. "The 'wow factor' of a conservatory can be pretty incredible."

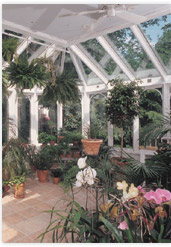

To sample the "wow factor" myself, I stepped into a large Amdega/Machin conservatory that had been built onto the back of an imposing

Georgian-style house by Paul Zec in Greenwich, Connecticut. With its tan stucco walls, the austere house seems every inch from the

21st century, until visitors step into a sage green conservatory that extends into a rose garden. The lavish 15-foot-by-25-foot room

is used as a potting shed, a hothouse for growing flowers in cold weather and a year-round tearoom. While fully functional, the

conservatory's chief purpose is to delight the eye, says Zec, "like a jewel on the back of the house." With it's pointed Gothic

windows, four-sided endwall and fancy filigree running along the roof ridge, it evokes the Crystal Palace's marriage of elegance and

playfulness.

Not surprisingly, conservatories cost more than an ordinary addition. A small 100-square-foot "bump-out" for a kitchen that is large

enough to hold a table and four chairs might cost $40,000. The average-size addition amounts to a 10-foot-by-15-foot room, and might

cost between $55,000 to $60,000 says Jim Lacata of Town & Country Conservatories in Chicago, "But it can rise steadily from there."

The 15-foot-by-25-foot tearoom in Greenwich, for instance, cost $125,000 for the structure and shades alone.

One final challenge is finding a conservatory built in a style that matches or at least comes close to that of the existing house.

In the United States, the trend until recently has been toward add-on sunrooms and solariums, which have more prosaic origins than

English conservatories. "Say the words 'fast-food restaurant' and what comes to mind?" asks Lacata. "A curved-glass sunroom,

jutting out from a building; that's what a lot of people first imagine when they hear the world conservatory." But English-inspired

conservatories offer a range of styles, from Gothic, with pointed-arch windows, to Palladian, with curved ones, and even to Frank

Lloyd Wright's Prairie style, with its mix of rectangular glazings. "The key word is custom," says Barocco of Renaissance Conservatories.

"These spaces can be designed to blend or contrast with any style of house you can imagine."

The broad range of available styles can sometimes lead to il-advised choices and even outright mistakes, especially if an owner chooses a

conservatory design that strays too far from whatever the house looks like, or incorrectly mixes period styles. Not all traditional or

classic styles are meant for marriage outside their particular aesthetic domain, and anyone considering a conservatory addition should

consult with an architect whose portfolio contains some relevant work. Besides being a space that's comfortable and functional, the

end result of all the planning and designing should be two structures that look as though they were always meant to stand together.

Curtis Rist is the author of "Rapid Results: A 30-Day Fitness Plan for Real People" (Rodale Press), to be published in the spring of 2003.

|

|