|

Beth Keegan's Prairie-style home in Evanston, Illinois, was a historic gem-except for the small and dingy kitchen. A year after moving in, she and her husband, Keith Murnighan, began searching for a solution. A friend suggested adding a conservatory onto the space, but Beth was skeptical. "I had never seen a glass room whose style would get approval by our landmark commission," she says.

Keegan's lack of knowledge about conservatories wasn't unusual. "It's amazing how many people think a conservatory has to look like the thing hitched to a Burger King," says Jim Licata, president of Town & Country Conservatories in Chicago. Explaining what a conservatory is-and what it isn't-occupies much of his time. "It's not a greenhouse, a Florida room, or a sunroom," he says. Unlike a greenhouse, a conservatory is a structure designed for people, not plants, and its glass roof distinguishes it from other glassed-in rooms. Framed most often in rot-resistant mahogany or red cedar, sheathed in glass, and climate-controlled, conservatories provide a comfortable, year-round living space. Styles range from an add-on with a simple lean-to roof to a freestanding mini-Crystal Palace with a soaring clerestory, graceful muntin patterns, and ornate rooftop crestings and finials. "They can be family rooms, dining rooms, playrooms-whatever the homeowner wants," say Licata. Well, with a few exceptions: "We gently discourage requests for a bathroom or bedroom," he says.

The Keegan-Murnighans warmed to the idea of a conservatory after David Bishop, a designer and builder of these specialized structures, showed them the difference between mass-produced modular units and one of his custom creations. "When I saw his portfolio, I knew that one his designs would fit perfectly on my house," says Beth. Bishop framed out a five-sided addition connected to the kitchen via French doors, assembled it atop a foundation, and attached the glazing. Now, no matter what the weather outdoors, Keegan, Murnighan, and their three kids gravitate to the conservatory, where it's always a perfect 75 degrees. "It's glorious," says Keegan. "It's changed the whole house, and the way we live in it."

|

|

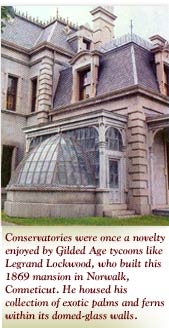

The roof of their addition was manufactured and shipped over from England, the mecca for conservatory cognoscenti. In the 19th century, the English perfected the skeletal wood or iron frameworks that could be wrapped in glass from roof to sill. These were sold by the thousands to prosperous clientele captivated by the notion communing with nature from a comfortable perch-comfortable at least some of the time. Earlier generations of single-glazed rooms could be cold, wet, and drafty in the winter, and unbearably hot in the summer.

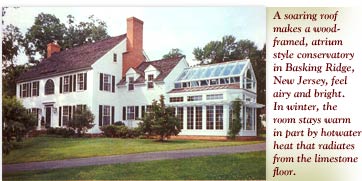

To improve insulation in the winter, today's conservatories have double-glazed panels that are tightly weatherstripped to hold in heat and prevent condensation; working windows-ideally at least a third of the structure's surface-ventilate the room in warm weather. But to really live comfortably under glass year-round, Licata suggests installing a separate forced-air heating and cooling system. Radiant-floor heating is icing on the cake. "I often walk in and find my kids lying on the ground to watch the snow fall," he says. And for every hot day the air conditioning labors to keep the room cool, there's a cold day when the conservatory provides free solar warmth to the rest of the house.

If all this sounds expensive, that's because it is. David C. Bishop & Co.'s conservatories cost between $40,000 and $60,000. The price varies depending on the size of the room-250 square feet is typical-and the detail of the design. "But what you get," insists Licata, "is a room you never want to leave." Beth Keegan says that when the family isn't in bed, they're probably in the new 500-square-foot addition. "Sometimes," she says, "we joke that we might as well get rid of the rest of the house."

|

|